We at TrendSource eat, breath, and sleep market research. So when we are looking to unwind after hours, we sit around and get excited about some really dorky marketing and market research things. A few weeks ago, somebody got us talking about some of the biggest market research fails (read: disasters) in memory and, after kicking it around for a while, we thought we’d turn it into a blog.

So follow us through the ten biggest market research failures of the last 100 years. And then call us to make sure you don’t make the same mistakes.

Colgate Frozen Entrees

Some of you may be too young to remember (ok, some of us too) Colgate’s ill-advised foray into frozen dinners, but in 1982 the toothpaste producer sought to branch out of center-aisle CPG and into the frozen food section. Perhaps they thought customers would enjoy chomping through a Colgate chicken-and-peas dinner before cleaning their pearly-whites with a pea-sized dollop of Colgate toothpaste? Some kind of closed system for the digestive system? Frankly, it’s somewhat difficult to know what they were thinking.

Regardless, the expansion was unwise. Consumers had long associated Colgate with oral hygiene, and could not extend that brand association to food products like TV dinners. And while clean teeth certainly are attractive and desirable, toothpaste itself is not very appetizing. This, as marketing professors have taught aspiring MBAs ever since, is a classic lesson in brand extension: don’t ask customers to radically shift their understanding of your brand. Maybe if Colgate had come up with an entirely new name (through rigorous market research, no doubt), we would all be chowing down on some of their chicken-and-peas right now.

Playboy Magazine Becomes a Never Nude

This is not going to tread into NSFW territory, we promise. But a little over a year ago in March 2016, Playboy magazine (whose reputation hopefully precedes it), decided it should no longer feature nudity and published its first non-nude issue and even released a safe-for-work app.

It’s one thing to make a few subtle changes to stay current, but Playboy threw the baby out with the bathwater and alienated a customer base whose, um, tastes, were not that difficult to accommodate. One year after the change, the brand had lost its identity entirely. While they had made the change to increase the publications’ reputability and sharability in digital forums (few people want to share a link to Playboy on Facebook), their market research did not account for who would be doing the sharing once the brand had lost its cache and failed to draw eyeballs.

Exactly one year after the change, the new Playboy chairman concluded the experiment was over, and the Bunny Emperor could go back to not wearing any clothes. In hindsight, according to the new chair, it “was a bad idea, the whole thing.” It remains to be seen if the periodical will rebound, but there is at least one other take away from the Playboy experiment: for precisely one year, one could claim they only read Playboy “for the articles,” and not be immediately dismissed as a liar.

Starbucks Mazagran

For every Unicorn Frappuccino, there is a Mazagran.

In the mid-1990s, Starbucks partnered with Pepsi to sell Mazagran, a coffee-flavored, bottled soda found in grocery aisles. The product was a spectacular failure—described as tasting “interesting” at best—and was pulled within a year as sales declined after initial curiosity waned.

But maybe they needed to fail before they could succeed. Because the thing is, Starbucks got this one half right. Their market research had correctly told them that customers wanted a cold, sweet, bottled coffee beverage they could conveniently purchase in grocery stores. They just wanted it to resemble a milk shake, not a soda. Though it is impossible to prove, Starbucks urban legend even suggests that the idea for the Frappuccino was born out of Mazagran’s failure.

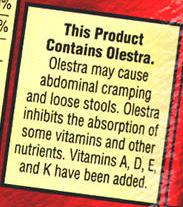

Wow! Chips

Who doesn’t remember the potato chips that moved through us like the Norovirus?

Fried in Olestra, a sucrose-derived oil not absorbed by the body, Frito-Lay’s Wow! chips carried 1/3 the calories and none of the fat of their traditional crispy cousins. The late-1990s product came under Doritos, Ruffles, and Lays brands and, owing to the misguided low-fat diet craze of the era, initially sold like lowfat hotcakes. Within a year, however, sales had dropped by almost $150 million after the FDA forced the chips to carry a warning label advising they can cause, well, let’s just say gastrointestinal distress.

This was a market research failure of product testing, pure and simple. While exhaustive rounds of taste tests were no doubt performed, it would seem that none of those taste tests ever pushed past the suggested serving size. You see, Olestra is fine in small doses and issues only percolate when binge eating (also known as typical US snack-eating behavior) is involved. Thus, by overestimating Americans’ ability to eat just one (oh, the irony!) Frito-Lay walked themselves into an explosive disaster.

Celery Jell-O

It’s easy to look back on this one and say, well duh…because the thought of a seafood salad suspended in celery Jell-O is about as appetizing as…I got nothing, it just sounds disgusting. But remember, the product was coming on the heels of the late 1950s and early 1960s—an era of casseroles, tang, and the ambrosia salad. And lime Jell-O had long been used in the suspended salad craze, so they thought they’d help customers out with some savory Jell-O flavors. They were a bit late, however, as their 1965 release date came on the heels of the savory suspended salad trend.

The other problem? It did not taste good, holding a salad together or otherwise. They had, to quote a cinematic chaos theorist, been so worried about whether they could build something that they forgot to ask if they should. Customers continued using Lime Jell-O off-label for their savory recipes, and the vegetable flavor quickly disappeared.

Apple Newton

The classic example of being ahead of your time. The Apple Newton was an early PDA device that could take notes, store contacts, manage calendars, send faxes, and even translate handwriting to text (in theory).

That last point was the biggest problem, it turned out. By rushing the product to market before ironing out the handwriting to text feature, the company opened itself up to popular ridicule. In Doonesbury cartoonist Gary Tradeau’s hands, the Newton became a symbol of yuppie extravagance and excess—they were spending hundreds of dollars to buy hand-held computers to take inaccurate notes when a pen and paper could do it for a miniscule fraction of the cost. And without errors.

Market research will tell you consumers are enthusiastic about a potential new tech product. But only if that product works as advertised. If you can’t meet their expectations, your product is doomed to fail, no matter how high those expectations were.

Of course, nowadays, the technology has caught up to the market research and the personal handheld computer is so commonplace we can’t imagine a world not eagerly awaiting the next iPhone. But in the ‘90s, it was just ahead of its time.

3DTV

This isn’t one brand in particular but TV manufacturers in general. Right around the time Avatar raked in its second billion dollars, TV-makers decided the iron was hot: Americans were ready for 3D TVs. Manufacturers pumped untold resources into developing units that were as non-disruptive and immersive as possible.

There were a couple of market research problems. First, everybody just assumed demand was there based on Avatar’s success. But in the hands of almost anybody not named James Cameron, 3DTV isn’t all that great: it requires glasses, eliminates second-screening, and gives some people headaches and neck strain. So while there was temporary enthusiasm in focus groups around the country, manufacturers mistook a flash in the pan for signs of a gold strike.

The second problem was an even bigger one, and frankly one that any market researcher worth her salt would have seen coming: even if the 3DTV works to perfection, what content will people watch on these magical boxes? Since the 3D movie craze died (did we really need Clash of the Titians 2 to be in 3D?) and channels like ESPN discontinued their 3D feeds, the answer is Nothing.

With LG and Sony discontinuing their models, no major TV-makers manufactures currently offer 3D TVs, moving this one firmly into the loss column.

Netflix and Qwikster

This should go without saying, but don’t make things more difficult for your customer in order to make them easier for you. Just ask Qwikster, errr, Netflix.

Realizing it was time to phase out its DVD mailing program in order to focus on streaming, Netflix briefly split into Netflix and Qwikster, forcing customers with joint DVD and streaming accounts to sign up for two separate services. That meant two different accounts and two different bills where there had been one. From Netflix’s perspective, this was tidier, eliminated confusion, and made both services better. They had failed to test and consider user experience and customer sentiment.

While the company certainly was correct about the destination—who, beyond the person looking for a copy of that one great independent French film they saw ten years ago, even gets DVDs from Netflix anymore?—they took the wrong path. Customers felt put upon and herded, and Netflix quickly reversed course.

Ford Edsel

In the late 1950s, the Ford Edsel was supposed to be a game changer, the new American car for the New American family. And that, right there, was a big part of why it failed—supremely high expectations. For all the promises Ford made in marketing campaigns before the debut, you would have guessed it doubled as a washer-dryer and space ship. And then, after all that promise, it was just a car. And not a great performing or cost-effective one at that.

The thing is, Ford did the market research—lots of it. But they used it in an effort to appeal to everybody instead of identifying and attacking a particular segment. Thus, the Edsel debuted in 18 different models and varieties and was dubbed the “Ford Hermaphrodite” but confused consumers. Combine that with an almost-immediately mocked front grille roughly the size of Detroit, a gas guzzling engine even by contemporary standards, and a perplexingly bad name you arrive at a product failure so famous, Billy Joel put it in a song.

Crystal Pepsi

When Crystal Clear Pepsi debuted in the mid-1990s, clean and pure were buzzwords much like they are today. Miller had debuted Zima, a clear malt liquor also destined to fail, Ivory was abandoning the milky for the clear, and even EBSCO gasoline was being touted as crystal clear. So, looking at their market research, Pepsi decided to jump into the clear market with Crystal Clear Pepsi, a transparent, caffeine-free soda that tasted exactly like Pepsi.

Pepsi saw the writing on the wall, it just misread it.

Yes, customers were interested in clean and clear products and they still are today. They just didn’t think of Cola as one of them. They wanted their cola brown and full of caffeine, they wanted their clear sodas light and crisp like 7-Up.

Pepsi had used market research to conjure a niche market—consumers craving a visually different, but similar tasting, caffeine-free version of Pepsi—where one simply didn’t exist. Of course, nostalgia can freshen up even the smelliest ideas and Pepsi will be relaunching the beverage in a limited capacity this year

New Coke

Because no survey of product failures would be complete without at least a cursory tip-of-the-hat to New Coke.

Facing waning sales and a perception that Pepsi tasted better (those Pepsi Challenge taste test commercials worked!), Coke began testing a new formula and released it in 1985. Though focus groups had been extremely favorable to the new taste—ranking it ahead of both Pepsi and the Classic formulation—the product was a sales and public relations disaster.

Coke had been so focused on flavor superiority they had failed to consider the intangible nostalgia and familiarity people attached to the classic flavor, and failed to account for the ways popular opinion can snowball and trump a simple taste test.

Consumers boycotted the brand, launched protests, and even hoarded cases of the Classic variety. Acknowledging the mistake, they phased out the brand slowly, but not before going down in history as the single greatest failed product launch of all time.

But it wasn’t all a failure. The move ultimately reminded people of their deep bonds with the brand which extended beyond flavor, dramatically turning around the brand’s fortunes. It remains the best-selling soda on the planet.

The Male Romper?

One final entrant, though it is only included under duress.

Some members of the TrendSource team insist the male romper is a product failure in-the-making. They say there is no market for this fashion, and that those who wear it will subject themselves to ridicule and alienation. They don’t need all the investigative might of our market research company, because they already know it for a fact.

But, according to this humble blogger, these people are wrong.

Male rompers are adorable and we will all soon be wearing them. Detractors are retrograde reactionaries clinging to their dated ideas of gendered fashion. They think it looks silly. But look at that man and tell me “silly” is what comes to mind.

Yeah, I thought not.